In the

January issue, we started to cover the story of the Canadian Martyrs.

This month, we are pleased to give you a report on the life of St. Noel

Chabanel.

In the

January issue, we started to cover the story of the Canadian Martyrs.

This month, we are pleased to give you a report on the life of St. Noel

Chabanel.

ST. NOňL CHABANEL (1613 Ė 1649)

St.

NoŽl was the last of the eight Canadian martyrs to suffer martyrdom.

He was born in France, in the village of Saugues on February 2, 1613.

His father, a notary, and his mother raised him and their three other

children firmly in the Catholic faith. NoŽl was first educated in the

Chapter school of Saugues and later he went to college. When he was

seventeen, he entered the Jesuit Order in Toulouse in 1630. NoŽl was

a novice for two years and during this time he studied and practiced

the rules and constitutions of the Jesuit Order. He especially strived

to be more and more humble and to deny himself, making many sacrifices.

Later in life, humility and self-denial would be two of NoŽlís outstanding

virtues. After being in the novitiate for two years and making his first

vows, he taught rhetoric at the Toulouse College from 1632 Ė 1639.

St.

NoŽl was the last of the eight Canadian martyrs to suffer martyrdom.

He was born in France, in the village of Saugues on February 2, 1613.

His father, a notary, and his mother raised him and their three other

children firmly in the Catholic faith. NoŽl was first educated in the

Chapter school of Saugues and later he went to college. When he was

seventeen, he entered the Jesuit Order in Toulouse in 1630. NoŽl was

a novice for two years and during this time he studied and practiced

the rules and constitutions of the Jesuit Order. He especially strived

to be more and more humble and to deny himself, making many sacrifices.

Later in life, humility and self-denial would be two of NoŽlís outstanding

virtues. After being in the novitiate for two years and making his first

vows, he taught rhetoric at the Toulouse College from 1632 Ė 1639.

From 1639 Ė 1641 he studied theology at this same college and in 1641 he was ordained a priest. After Fr. Chabanel was ordained, he taught rhetoric at Rodez, and in 1642 passed through the final stage in the formation of the members of the Jesuit Order.

From the Jesuit Relations, (news about what was going on in the different Jesuit missions in many parts of the world), Fr. Chabanel learned of the heroic work of his fellow Jesuits in New France. Burning with desire to serve God in the missions of New France, he wrote to the Superior General of the Society asking for permission to go there. NoŽl received a reply in November 1642, but was not allowed to go. He waited patiently and later, wrote again. Finally on April 4, 1643, he received a reply from the Superior General allowing him to go to New France. On May 8, 1643, he boarded a ship and sailed for New France. The trip would last ninety-six days and there was lack of space on the ship as well as a mixture of all classes of people and lack of cleanliness.

The affairs of New France were in bad condition. The people were short of many different supplies and they feared that a disaster had taken place. But one day, as Fr. Vimont was about to begin Mass, two ships appeared and the colonists were filled with joy. Supplies had come at last, and better still, it was found that three Jesuit priests were on board the ships.

The Iroquois were frightening not only the French but the other Indian tribes as well. They were keeping constant watch along the St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers to stop both Hurons and Algonquin from reaching their destination, and what is worse; they killed all who fell into their hands. Because of these dangers and alarms, Fr. Chabanel and Fr. Garreau spent the winter of 1643 Ė 1644 in Quebec. At the same time they were most fortunate to have with them, Fr. Jean de Brťbeuf who was recovering from a broken collarbone. Fr. de Brťbeuf had been among the Huron Indians for over sixteen years. He knew their language, their laws, customs and superstitions, and many other things abut them. Thus he was able to give good instructions to the new missionaries so that their work would be successful.

With the Iroquois constantly on the lookout to catch and kill other Indian tribes; life was always dangerous. In the fall of 1643, Governor Montmagny had asked for soldiers from France, to help protect the budding missions. Some time later, the much needed soldiers had arrived from France so in the summer of 1644, Fathers de Brťbeuf, Garreau and Chabanel left Quebec along with a flotilla of twenty brave soldiers in an attempt to reach Huronia.

The next five years of his life, NoŽl spent at Ste. Marie and a few other missionary places, working first with Fr. de Brťbeuf and then with Fr. Garnier. Although Fr. Chabanel was an intelligent priest, he had a most difficult time trying to learn the Huron and Algonquin languages. Even after five years of study, he could hardly be understood even in the most ordinary conversation.

To make matters worse, NoŽl did not like the Indian life and the Indian customs and he saw nothing in them to please him. He was sick of their dirty cabins filled with the smell of smoke and vermin. He could not get used to the Indian food, even simple porridge made of ground Indian corn and water.

Fr. Chabanel continued trying to master the Indian language, even at the villages he went to visit, but in the villages, there was no privacy, and no separate room where he could study, and the Hurons were always watching him. He had no light but that given by the smoky fireplaces, and while reading his breviary or writing notes he was surrounded by ten or fifteen Indians, children of all ages, who screamed and cried and argued.

Fr. Chabanelís heaviest cross of all was that now and then, when God hid His presence from him, he felt abandoned by God. However, God would also shower this priest with special graces to help him realize that he was not alone and that God was helping him, in spite of his trial and crosses. NoŽl wrote that he was a ďbloodless martyr in the shadow of martyrdom.Ē

|

|

|

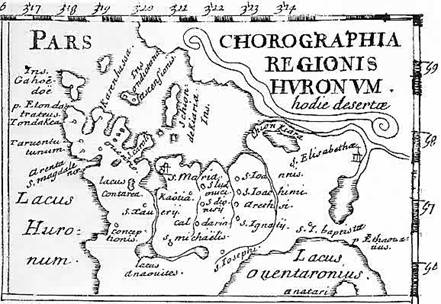

Map

of the Huronia Region |

NoŽl was tempted to give up his missionary work and return to France, to a better-suited way of living.

But instead of giving into the temptation, in 1647, on the Feast of Corpus Christi, he made a vow to remain in the missions of New France until his death.

In the spring of 1648, Fr. Chabanel aided Fr. de Brťbeuf and became his companion and assistant at the missions of St. Louis and St. Ignace. In February 1649, NoŽl was asked to go from St. Ignace to the Petun Nation. He was succeeded by Fr. Gabriel Lalemant who was martyred there a month later.

When Fr. Chabanel heard about Fr. Lalemantís martyrdom he was crushed in spirit. He too wished to be a martyr and had missed it by one month. But the saintly priest would not have long to wait for the martyrís crown he sighed for. Before the year 1649 was ended, the opportunity to suffer for Christ would come.

In the fall of 1649, Fr. Chabanel worked among the Petuns with Fr. Garnier at St. Jean. On December 5th, he again received orders to leave St. Jean and make his way to Christian Island. Two days later he learned that St. Jean had been attacked by the Iroquois and that Fr. Garnier had been martyred.

On his way, NoŽl stopped at the village of Matthias, a Petun mission where two other priests were stationed. On December 7th he left them accompanied by a few Christian Hurons. After travelling for some time on snowy roads, night came upon them. While his companions slept, Noel stayed awake and prayed.

Suddenly Fr. Chabanel heard the shouts and noises of Iroquois who had attacked St. Jean and their prisoners. NoŽl quickly awakened his companions who immediately ran for safety leaving the priest alone. When the Christians reached the Petun nation, they reported that Fr. Chabanel tried to follow them but when he could no longer keep up with his companions he fell on his knees saying, ďWhat difference does it make if I die or not? This life does not count for much. The Iroquois cannot snatch the happiness of heaven from me.Ē

On December 8th, NoŽl continued toward Christian Island. Louis, a Huron apostate, snuck up and killed NoŽl by hitting him with a hatchet, and then threw the priest`s body into the river. Later, Louis bragged that he had done this out of hatred for the Catholic Faith because of the crosses he had received when he became Catholic.

St. NoŽl Chabanel, Pray for Us††††††††††††††††††† ††††††††††††††††††††††† The End

Home | Contact

| Mass Centres | Schools

| Pilgrimages | Retreats

|

Precious Blood Residence

District Superior's

Ltrs | Superor General's

Ltrs | Various

Newsletter | Eucharistic

Crusade | Rosary Clarion | For

the Clergy | Coast to Coast |

Saints | Links